The collatz conjecture, first proposed in 1937 by Lothar Collatz, is a problem that seems simple, but has confounded mathematicians, who have been unable to prove or disprove it, for decades. So, without further ado, here is a simple proof of the collatz conjecture.

Background

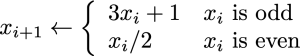

Starting with a positive integer x0. New integers can be computed using the following recurrence relation.

The Collatz recurrence relation.

Using this recurrence, a graph can be built that connects inputs of the recurrence to its output, as shown below.

Partial functional graph of the collatz recurrence.

The collatz conjecture is that for any positive integer, applying the recurrence will eventually produce the value one.

Proof

Binary Encoding

One aspect of the collatz problem that makes it tricky to understand is that the values fluctuate wildly, often reaching much higher values before eventually coming back down. However, a binary encoding of the numbers reveals several useful patterns.

| Operation | Decimal | Binary |

| Initial (x0) | 3310 | 1000012 |

| Multiply by 3 | 9910 | 11000112 |

| Add 1 | 10010 | 11001002 |

| Divide by 2 | 5010 | 1100102 |

| Divide by 2 | 2510 | 110012 |

Among the more useful patterns are:

- Low order bits and high order bits are all affected by multiplication.

- Only the lowest order bits are affected by the addition of one.

- Division by two removes one low order zero from even numbers.

Definitions

In this proof it will be necessary to refer to a particular bit within a binary number. For this, the function lob(x) gives the lowest order non-zero bit in x.

Using the observation that only low order bits are affected by the addition of the one, while higher order bits are only affected by the multiplication by 3, any sufficiently large integer can be decomposed into two regions of bits, a multiplicative region (MR) and additive region (AR), as follows.

![]()

Division-free Collatz

Using the observation that division only removes trailing zeros, without loss of generality, those zeros can be left in place resulting in an equivalent recurrence that is division-free.

A division-free Collatz recurrence relation.

Using this recurrence, the updated conjecture is that xi will eventually reach a power of 2.

When viewed in binary, this alternate formulation of collatz differs from standard collatz only in that a large number of zeros will accumulate below the low order bits.

Growth Rates

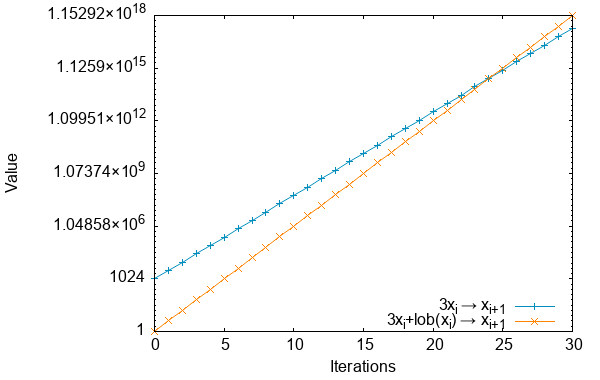

Recalling that any number can be decomposed into an MR and AR. The MR is only multiplied and can therefore only grow at a rate bounded by O(3ˣ), or 1.5 bits per iteration. The AR however has lob(xi) added to it each iteration, causing it to grow at a faster rate (approximately O(4ˣ)), or 2 about bits per iteration. The graph below shows how simply multiplying by 3 grows much more slowly than multiplying by 3 and adding the lob(xi). This means that the AR will grow faster than the MR, and will eventually overtake the MR, allowing the carry bit to pass all the way through to the highest order bit, leaving a single one bit (i.e., a power of 2) after the addition.

Relative growth rates of 3xi→xi+1 and 3x+lob(xi)→xi+1 (semi-log).

Since the AR consumes low order bits faster than the MR can add new high order bits, the total number of bits between the highest and lowest order bits will decrease overall, and will eventually reach zero, at which point x will be a power of two. Similarly, for standard collatz, had all of the divisions been performed it will reach one.

Therefore the collatz conjecture is true. Q.E.D.

Conclusion

Using a decomposition of an integer into regions based on how multiplication by three and addition of one affect the bits of binary number and examining several carefully chosen properties of binary arithmetic, it can be shown that the low order bits grow at an asymptotically faster rate than the higher order bits, eventually overtaking them.

Thus the gap between the highest and lowest order bits must shrink over time, eventually converging to a single one bit, thus proving the collatz conjecture to be true. . . April Fools!

Clearly, a problem such as the collatz problem which has confounded so many for so long, should require a much more complex proof than this. Therefore, this simple proof must contain some critical flaw. Can you spot it?

Check back next week for an explanation of the flaw.

Pingback: The Collatz Conjecture: A Simple Counterargument | Doing Science To Stuff